SOME OF THESE DAYS

One day in Chicago, Sophie's friend and traveling companion Mollie Elkins introduced her to the young Black composer Shelton Brooks, who had contacted Sophie about singing his new song, "Some of these Days." Sophie first recorded it in 1911 and it became her trademark song.

Brooks went on to write the popular early jazz standard "The Darktown Strutters' Ball," debuted by Sophie in her vaudeville act and made famous by The Original Dixieland Jass Band, considered the first commercially recorded Jazz band. (Their 1917 recording was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame in 2006.)

While headlining in Chicago, Sophie developed an act with Frank Westphal; the two were married in 1917. The duo performed together until, in her telling, the discrepency in their incomes broke the marriage for good.

Since I've been in show business I have been married twice. Both marriages were failures, due- as I can honestly say- to my earning capacity.

THE QUEEN OF JAZZ

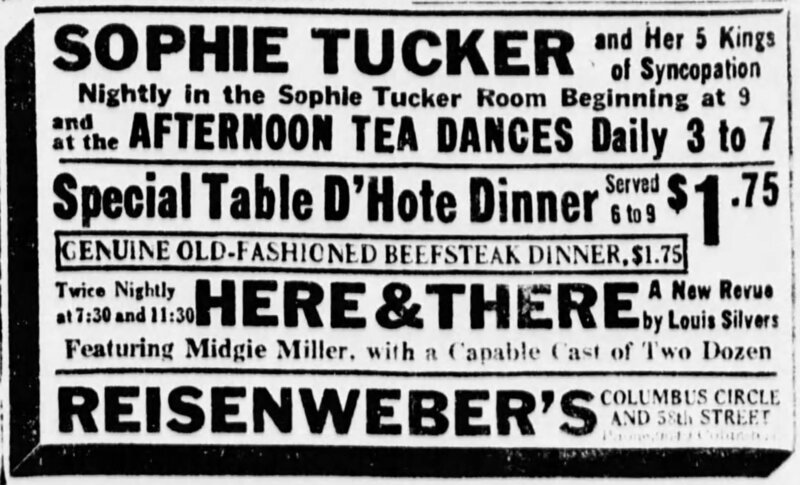

In the new cabaret scene in New York, Sophie transitioned away from traditional vaudeville, booking nightly performances as a dinner performer at Reisenweber's Cafe, an innovative restaurant with multiple floors boasting different kinds of entertainment on each level.

While performing at Reisenweber's, Sophie landed a spot in the Shubert Gaieties of 1919 at the Winter Garden, her first Broadway role.

J. J. Shubert sent for me to be the headliner at his Sunday-night concerts. I was cashing in on my success at Reisenweber's, but I can tell you it took some hustling to do it. I would go on at Reisenweber's for the dinner show, jump into a taxi, and race over to the Winter Garden to change my dress and close the bill of the Sunday-night concerts; then back to Reisenweber's and another change of costume for the late supper show.

As dinner entertainment evolved from ballroom dancing to early jazz bands, Sophie formed The 5 Kings of Syncopation, a group of young performers she mentored at the very outset of the Jazz era. She began billing herself as "the Queen of Jazz". Sophie's 5 Kings of Syncopation were contemporaries of the Original Dixieland Jass Band (later "Jazz"), who also got their start playing dinners at Reisenweber's.

Sophie's "Bohemian Nights" at Reisenweber's were so popular that the proprietor renamed his "400 room" the "Sophie Tucker Room" in 1919. It was at Reisenweber's that Sophie met Al Lackey, who would become her third husband.

As Prohibition took hold, the restaurant was subject to frequent liquor raids and was closed for good in 1922.

Oh, but New York was gay in that year right after the war. The town was full of men just home from France and hungry for fun, laughs, gay songs, pretty girls. Cabarets - how the word had taken hold! - were springing up all over town and doing big business, though everybody was wondering what Prohibition was going to do to them and to the whole entertainment world. I don't think anyone guessed what we really were in for - that is, the Speak-easy Era. But everybody in the cafe business felt jittery, and wondered what would happen after the Volstead Act went into effect.

A keen marketer, Sophie Tucker tried to make sure her name appeared on sheet music for the songs she performed in the 1920s.

AMERICA'S FOREMOST JEWISH ACTRESS

In 1920 Sophie divorced her husband Frank Westphal after their act together deteriorated. In 1921, she hired Ted Shapiro to accompany her on piano. Their professional relationship lasted for 40 years.

In March of 1922, Sophie sailed for London to "show the British what American jazz was like."

Everything about the trip across was wonderful to me. Not the least wonderful was the thought, how different this trip was from my first one coming to America in the steerage. Thinking about that, I could realize something of the meaning of America, the only country on earth where the sort of thing that had happened in my life could happen. America had given me the opportunity to make good. I owed it everything I had. Now I was going back to Europe in a way to represent America to audiences. It was going to be up to me to show the British what America can do for an immigrant girl.

Sophie brought along her new pianist, Ted Shapiro, and an alternate, Jack Carroll, and debuted the first double piano performance in London.

Always a quick study, Sophie realized that she would have to change her act to accommodate English audiences. With slower tempos and British phrases substituted for American lyrics, she quickly endeared herself to London society.

All the all-American words we changed to British equivalents. Gas became petrol, nickel and dimes, bobs and tuppences. Meanwhile, Ted and Jack and I went to work on slowing up all the songs. I've always been proud of my timing; it's something I've worked at ever since I've been in show business. ... My figure may bulge, but my act is streamlined.

In an act of remarkable business savvy, Sophie sought out and performed at Jewish benefits in London before officially debuting on stage, building goodwill and name recognition among her co-religionists. When a huge crowd gathered for her last few shows in London, she saw a banner proclaiming, "WELCOME SOPHIE TUCKER, America's foremost Jewish actress" - which she said made her prouder than anything else.

MY YIDDISHE MOMME

In 1925, Sophie's mother was ailing, and Tucker performed a song written by the talented composer Jack Yellen, "My Yiddishe Momme," reflecting a bittersweet yearning for a beloved and departed mother. Sophie was sailing back from England when she learned that her mother had died. The song, sung in both English and Yiddish, became a huge hit; the 1928 Columbia record sold over a million copies.

Always aware of her audience, Tucker recalled, "Even though I loved the song and it was a sensational hit every time I sang it, I was always careful to use it only when I knew the majority of the house would understand Yiddish. However, you didn't have to be a Jew to be moved by 'My Yiddishe Mama', 'Mother' in any language means the same thing." Indeed, it was a hit among both Jewish and non-Jewish audiences alike.

"Whenever I could, I'd run up to Hartford for a few hours with Ma and Pa. I always tried to be with them for our High Holidays, knowing much it meant to them to have all their family with them at these solemn times. I knew Ma would boast to her buddies about 'mein Sophie' that was a headliner and made so much money coming home."

She performed the song to varied audiences throughout the U.S. and Europe, where it became a kind of anthem after it was banned by the Third Reich and her records were ordered to be smashed. The song evoked a reverence for Jewish culture and a cultural memory of more peaceful times, and was thus threatening to Hitler’s regime. At a 1932 performance in France, Tucker started to sing the song in response to audience requests, but when she reached the second verse in Yiddish, people started to boo so loudly she had to change songs.

Several years later, after Hitler came into power and started the persecution of the Jews in Germany, I heard that my records of "My Yiddisha Mama" were ordered smashed and the sale of them banned in the Reich. I was hopping mad. I sat right down and wrote a letter to Herr Hitler which was a masterpiece. To date, I have never had an answer.