Sophie arrived in the big city determined to succeed. She made the rounds of music publishers, trying to convince them, to no avail, that she could sing their songs. She changed her last name to Tucker and started working for tips and meals in small cafes and beer gardens.

I found a room for five dollars a week, which included breakfast, on Second Avenue near St. Mark's Place. I lived there for several weeks while I tried all the doors in Tin Pan Alley without success. Meanwhile my funds were running low. ... One evening it occurred to me perhaps I could sing in one of the restaurants in the neighborhood and earn a meal that way. Around on Eighth Street was the Cafe Monopol. I went in and said to the proprietor: "I'm hungry, and I haven't any money. I'm a singer. If I sing for your customers tonight will you give me my dinner? ... I'll sing what the customers ask for. I used to do that in a restaurant in Hartford, my home town.""All right," he agreed. Then he asked my name.I had my mail sent to Mrs. Louis Tuck, care of General Delivery, as of course that was my name. But "Mrs. Tuck" didn't sound right for a singer. "Sophie Tucker," I told him.

Finally, she was hired by The German Village club, where agents stopped by looking for new talent. Each night, she belted out 50 to 100 songs and earned her keep. Times were tough, but Sophie always sent a few dollars home.

GET SOME CORK AND BLACK HER UP

An agent soon spotted Sophie and suggested she audition for the 125th St. Theater. The audiences were boisterous, and she overheard the owner declare, "This one's so big and ugly the crowd out front will razz her. Better get some cork and black her up. She'll kill 'em." Rather than miss the opportunity to get on stage, Sophie put up with the insult and tried to make the best of the situation.

"Let me leave off the black," I pleaded. "Try me out the way I am and see if I don't go over." But he wouldn't hear of it. That's how I became a blackface singer.

She soon learned that immigrant performers were the primary racial impersonators in vaudeville shows. Immigrants quickly learned how to get laughs by reproducing old minstrels’ blackface characters, or by impersonating their own ethnicity and an assortment of others. Performing in blackface (either using burnt cork or what she described as "high yellow" makeup) opened doors for Tucker and taught her the appeal of being able to portray a variety of stereotypical characters - a key to success in the world of vaudeville.

Within a few years, she began to introduce her Jewish identity as part of her act, as a way to connect with the largely immigrant vaudeville audience. She started to insert some Yiddish words into her songs and to talk about her Jewish upbringing, "just to give the audience a kick." On occasion, at the end of a performance, she removed her wig and gloves to show the audience she was white.

As she tells it, one day before a matinee show in Boston Sophie's luggage was diverted to Lowell, Massachusetts, and she had to go on stage without her costume or makeup.

The leader and the boys in the pit gaped at me. They expected blackface. So, of course, did the audience. I could see them consulting their programs. I'd have to explain. Somehow, telling them about the trunk that had gone on to Lowell by mistake started me getting even more confidential."You-all can see I'm a white girl. Well, I'll tell you something more: I'm not Southern. I grew up right here in Boston, at 22 Salem Street. I'm a Jewish girl, and I just learned this Southern accent doing a blackface act for two years. And now, Mr. Leader, please play my song.""That Lovin' Rag" got them started. They were right with me. All the time I was singing five numbers, six, seven, then an eighth, inwardly I was exulting: "I don't need blackface. I can hold an audience without it. I'm through with blackface. I'll never black up again."

While she stopped performing in blackface as her star rose in the theater world, Sophie continued to explore various kinds of racial and character impersonation through different musical styles with roots in Black culture (ragtime, jazz, blues, swing, the hep-cat, jitterbug, and zoot-suit) and to perform with a multiracial cast of dancers and musicians. When she sang in a Black Southern accent, in Yiddish, or a mix of both, she was sometimes billed as ‘The Jewish Girl with a Colored Voice.’

In 1909, Sophie had an opportunity to perform with the Ziegfeld Follies in Atlantic City. After feeling ignored during rehearsals, she promised herself she would "stop the show cold" on opening night - and she did.

Through eight weeks of rehearsals not one member of the Follies' management or cast ever heard me sing a note. ... I couldn't understand it.I looked at the dress the wardrobe mistress had made for me ... I thought of the three songs Irving Berlin had selected for my act: two of his, "The Right Church but the Wrong Pew" and "The Yiddisha Rag," and "The Cubanola Glide" by Harry Von Tilzer. ... I knew those songs were smash hits. I knew I could sing them. I knew when I tried on the gold gown that I looked stunning. ..."I'll tie the show up in a knot," I promised myself. "Suppose that big finale number did cost forty thousand dollars to produce and all they want me for is to fill in time while they get it set. They're going to see something tonight. I'll hold up that forty thousand dollars' worth of finale or my name isn't Sophie Tucker."

When the crowd demanded she return to sing more songs, the stagehands were forced to stop the next number. Nora Bayes, who had top billing, was furious and forced Sophie out of the Follies.

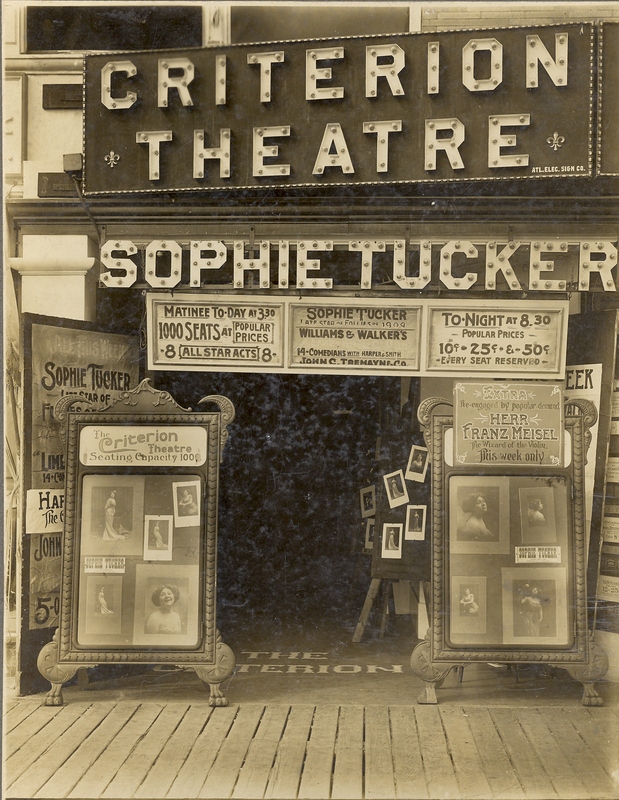

After the Follies debacle, a rising agent, William Morris, signed Sophie and booked her in music halls. Performing as a headliner act in Chicago, New Orleans and San Francisco, Sophie delighted her audiences with comedy and bawdy songs. She stayed with the Morris Agency for over fifty years.

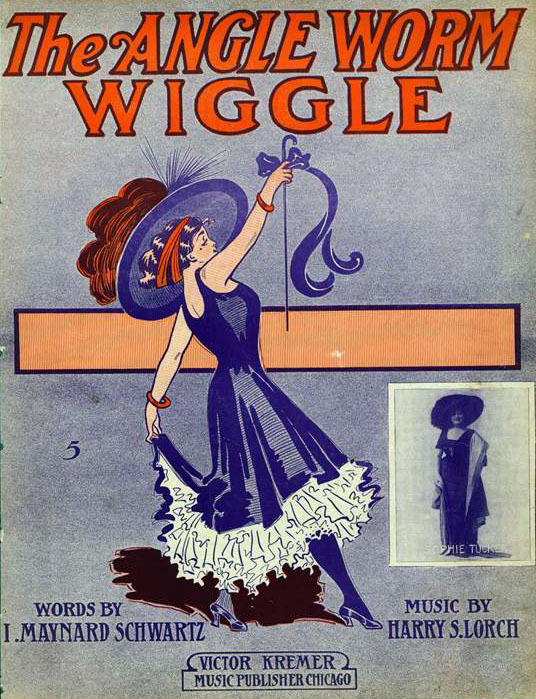

THE ANGLE-WORM WIGGLE

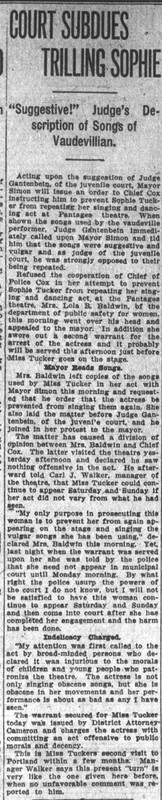

In 1910, on tour at the Pantages Theatre in Portland, Oregon, Sophie was arrested and charged with indelicacy and vulgarity when a representative of the department of public safety for women complained to the mayor.

The song itself had nothing to it (it was a gospel hymn compared to some of the numbers you hear today), but I got a jeweler to make me four rings of big green stones which I could wear on the second and fourth fingers of both hands to glitter as I used my hands snakily up and down my body as I sang, producing, as I hoped, a naughty effect to put the song across.After the first matinee Mrs. Baldwin swore out a warrant for my arrest on the grounds that my act was "immoral and indecent." I believe I was represented as a muscle dancer from the Barbary Coast. Of course the papers ate it up.The chief of police came to see the show and declared that my act was all right. He gave it as his opinion that "The Angle-worm Wiggle" was less indecent than some of the other acts on the bill which apparently hadn't brought a single blush to Mrs. Baldwin's cheeks. This made the lady furious. She took the matter to the mayor. She also swore out another warrant against me on the grounds that I had ridiculed her from the stage by ad-libbing as I wiggled my fingers up and down my torso, "very immoral."I put up fifty dollars bail and offered to sing any song the mayor, the chief of police, and Mrs. Baldwin should select to prove that my act was neither indecent nor immoral. When this offer was refused, my friends took me to the district attorney. I made the demand of him that he give me a jury trial at which I would sing "The Angle-worm Wiggle" for the jury. The D. A. read the lyrics and then threw out the case. He bawled out the mayor and Mrs. Baldwin and the whole kaboodle.I was left sitting on top of the world with pages and pages of publicity and a line at the box office three blocks long. The theater held me over for two more weeks, and I had to promise to play a return engagement before I went back East.